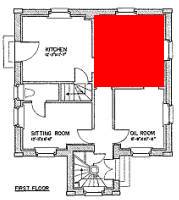

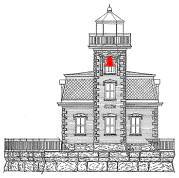

Keepers Room

There were several keepers that were stations here at this lighthouse over the years, the last civilian keeper being Emil Brunner. Our restoration efforts have focused upon the years in which he and his family lived at the lighthouse. This small room here on the first floor was his bedroom, as he had to be up several times during the night to check the light and refuel the lantern. The oil or kerosene for the lantern was stored in the basement and had to be brought up to the lantern room. The partial lens you see on the floor is one similar to that which would have been here. The original lens is in the South Street Seaport Museum in New York City.

Emil Brunner, the last civilian keeper was here from 1932 until 1949. The last person to tend the lighthouse was William Nestle, who oversaw the operations of the light and fog signal from 1966 until 1986. The first keeper was Henry D. Best. He kept the light until his death in January of 1983 and was succeeded by his son, Frank. Through the years the lighthouse had nine light keepers including one woman, Nellie Best, for a short time in 1918.

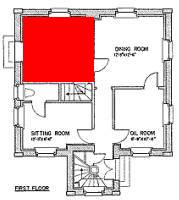

The Kitchen

The kitchen was the heart of the lighthouse, something was going on here a good part of the day with the preparation of meals, baking, and of course coffee. As was everything in the lighthouse, cooking methods were rather primitive. The coal stove meant that it was nice and warm in the winter bur a bit toasty during the summer months. Water was collected from the roof into a cistern located under the kitchen. It was then pumped by hand when needed, using the old fashioned hand pump on the sink.

There was no indoor plumbing until 1938 when a bathroom was installed inside the lighthouse as well as a central heating system that was run by a coal furnace. Up until then there was an outhouse that hung out over the river just to the right of the flagpole. A fun experience in the winter for sure. Laundry was done by hand in the old days, but the Brunners had an old gas engine washing machine. Ironing was done with a cast iron flat iron that was heated on the kitchen stove.

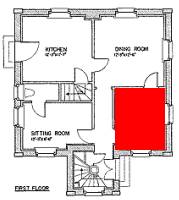

The Dining Room

The next room was the dining room. What a view for dinner! Today in this room are some Hudson River memorabilia in the display case along with a replica of a Keeper’s hat and badge. In the corner is a reproduction of a Lighthouse Service blanket.

Originals of these items in good condition are very hard to come by and are very expensive to purchase.

The Stairway

The stairs are narrow and winding. Please notice the brass hand railing. The Lighthouse Service was noted for all its brasswork. All of the fittings of the lens and lantern apparatus were made of brass as well as many other items found in the lighthouse such as dustpans, work boxes, oil lanterns, oil cans, etc. When the lighthouse was closed up in 1954 most of the brasswork was taken out. This railing is all that remains. Of course all of the brass was expected to be kept polished. The last verse of a poem written by Fred Morong, a Maine light keeper, circa 1920 goes like this:

“And when I have polished until I am cold,

And I’m taken aloft to the Heavenly Fold,

Will my harp and my crown be made of pure gold?

No, brasswork.”

These items as well as other supplies came from a central warehouse called a Lighthouse Depot, which for the Hudson River lighthouses was located on Staten Island.

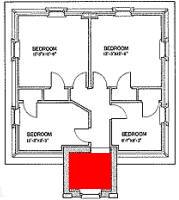

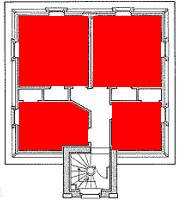

The Bedrooms

The second floor has four rooms that were used as bedrooms. The Brunners had five children, four of which lived at the lighthouse until the family moved into the Town of Athens in 1938. They were Emily, Richard, John, Robert (who was actually born in the lighthouse), and Norman who was born after the family had moved into town. Mr. Brunner of course remained at the lighthouse, while the rest of his family lived in town.

Raising four children in such a confined space must have been no small challenge. It is hard to imagine not having a yard or streets to walk down or other children to play with.

We are going to use these rooms on the second floor to interpret river life around the lighthouse and the waterfront industries of both Hudson and Athens. You will find some pictures of the children who lived here as well as some enlarged copies of old postcards from the Hudson and Athens area. The larger bedroom has some displays and pictures of boats that operated on the river. Also in the small room you will find a display of all the lighthouses, which were on the Hudson River – both past and present.

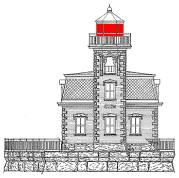

The Lantern Room

This is where the actual light of the lighthouse was. Before modern technology and automation, the keeper would have to keep the light shining. Every night he would have to light the lamps and make sure that they burned brightly and did not run out of oil. This usually meant several trips a night up and down the stairs. During the hours of darkness, the “light” was never to go out and if the Lighthouse Service received complaints that the light was not lit or that it was poorly lit, the light keeper would be in danger of losing his job. In the morning he would have to clean the soot from the lantern room, clean the lens, polish the brass, and make the lamps ready for the following night. This had to be done everyday. The lantern room as well as the entire lighthouse was subject to periodical inspection by a Lighthouse Service District Inspector. If all were not in ship-shape condition the keeper would be written up and warned. If the lighthouse continually did not meet the Lighthouse Service standards, the keeper would be replaced. However if all were well, he would receive praise and usually a written commendation. The Lighthouse Service had very strict regulations as to how a lighthouse should be kept.

The original light of this lighthouse was a fixed light, which was changed to a flashing light in 1926. It was a fifth order lens, being one of the smallest, but could still be seen as far away as one needed on the river. The light is 54 feet above sea level. Today the light is automated and is turned on at night by means of a light sensor. It is solar powered and maintained by the US Coast Guard.

The Fog Bell

The first fog bells were rung by hand, but around 1860, the Lighthouse Board installed mechanisms to ring them mechanically. Engines were used at first, but the “clock work” system as we have here (where the falling weight is the source of power) was soon adopted, as it was both more practical and reliable. The Hudson/Athens fog bell with the “clock work apparatus” is one of the few remaining in the United States. It rang once every fifteen seconds.

The fog bell chores of the light keepers improved with the installation of semiautomatic ringing mechanisms. The system here in the lighthouse is a weight and pulley escapement system that used weights that could be “wound” to start a timed session. Not unlike a grandfather clock, the system needed to be periodically rewound to insure that the fog bell continued to sound throughout the duration of fog conditions.

Should the escapement mechanism fail, the keepers then had to sound the bell manually, and at timed intervals and for the duration of the storm or fog. Consider the conditions of this effort between the hard and seemingly endless labor and the close-by clang of the bell. This dedication to duty and to the safety of others is a landmark of the US Lighthouse Service and its successor, the US Coast Guard.

By the 1920’s the Lighthouse Service had developed electrically operated bells. The bell by the front door of the lighthouse is an example of this type of fog bell. The US Coast Guard installed it in the 1940’s.

Today, sirens along with diaphones and diaphragm horns are the principle sound-type fog signals used in the United States. The last thirty or forty years has seen the development of the soundless fog signal: the radiobeacon and GPS (Global Positioning System), which uses satellites orbiting the earth to pinpoint your position.

The Middle Ground Flats

From the lantern room if you look to the north you will see an island. This is the “middle ground flats” and the reason for the building of this lighthouse. In the mid to late 1800’s this was just a mud flat, which was completely submerged at high tide. Many boat captains had wished that the lighthouse had been built much sooner as many ships found themselves grounded on the mud flats.

Through the years with dredging and the depositing of the silt, the “mud flats” have become an island. The main channel of the river is to the right, East, of the island towards the City of Hudson. The channel on the left, West, of the island towards Athens is navigable only for smaller boats.

The City of Hudson & Town of Athens

The city of Hudson was a well-established river port being founded in 1784 as a whaling port by a group of Nantucket whalers who relocated from the coast. They had feared that England would retake the colonies and wanted a safer place to run their whaling industry from. Hudson was one of several whaling ports on the Hudson River. It was also a stop for the Hudson River Dayliners, which carried thousands of passengers up and down the river form Troy to New York City.

Athens was a shipbuilding town. Many ships and boats were built in Athens including the 281-foot Kaaterskill, which ran for over thirty years between New York, Catskill and Hudson. The Athens Shipyard, the Clark Pottery, the Every & Eichhorn Ice house, and the Howlands Coal Yard were among many businesses that were located in Athens. These and other industries on the river all shipped their goods by boat. Many of the waterfront buildings were destroyed in the fire of March 23rd, 1935. There were also a number of ferries that ran from Athens to Hudson from as early as 1778 until the 1940’s. The ferryboats were doomed by the opening of the rip Van Winkle Bridge in 1935. All this combined with the hundreds of sloops, steamships, and barges that went up and down the river made this a very busy area on the river.

In the earlier days of navigation the lighthouses on the Hudson River were shut down for the winter season, usually from December to March as ice made the river impassible. During the winter the keepers would often engage in some seasonal employment to supplement the low wages that they received as a lighthouse keeper. Helping with the ice harvest was a common form of employment as the keepers lived on the river. But in later years the Coast Guard kept the river open with the use of icebreakers. Then the lighthouses remained operational all year.